Screenplay Format: The Basics of Writing (Part 3)

As In Any Endeavor, The Language of the Discipline Is Required Knowledge

June 16, 2023

Today we’ll be taking a look at screenplay format. Unlike most forms of writing, there is a set industry standard for the way a screenplay looks.

General Format

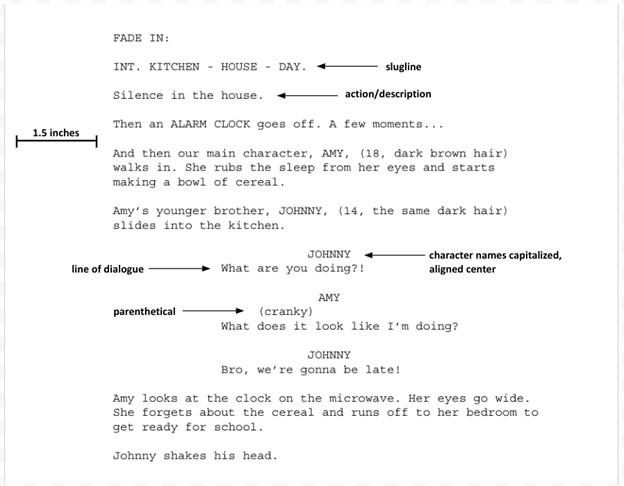

You may have noticed that each of the screenplay excerpts we’ve looked at so far have looked pretty much the same. Professional screenplays almost always use a 12 point single-spaced Courier font. The top, bottom, and right margins are all 1 inch, and the left is 1.5 inches to leave room for a punch hole in a hard copy of the script.

As far as alignment, the character’s name goes above their line of dialogue in all caps in the middle of the page. Everything else is aligned left. The one exception to this might be camera directions or camera cuts, like “CUT TO” or “SMASH CUT TO” which are sometimes aligned right. Usually these camera positions only show up in shooting scripts, which are the kind used on set.

It is worth mentioning a side note here: Screenwriting is a form of writing which can bend some grammar rules. Short sentences of two or three words are often used by screenwriters to create tension or speed up the action. You might even see something like this in a screenplay: “He stops. Turns around. Stares.” Technically that is grammatically incorrect, but it does add emphasis to each of the character’s actions and creates suspense.

Parts of a Screenplay

A screenplay has two main parts, description/action and dialogue. A typical scene will begin with description, so the setting can be established, and then will continue to have action dispersed between characters’ lines. However, some scenes are without dialogue, and others are without description. The latter is much less common, since screenplays are very visual and usually require at least some description in order to form a picture in the reader’s head of the scene taking place. Some screenwriters go heavy on this part of a screenplay, others don’t use much at all. But in general, description in a screenplay is much simpler and shorter than you might find in a book. In addition, when the character first appears in the description of the screenplay, their name is in all caps.

Dialogue is the other part of a screenplay. Longer screenplays are usually the length they are because they have a lot of dialogue in them. For example, a sequence of action you read in the screenplay of an action movie will take less time to see in the movie compared to how long it takes to read it off the page. In contrast, dialogue generally takes longer, with actors taking natural pauses and especially if there is any action in between lines. Dialogue is arguably the most important part of a screenplay, because without well-written dialogue, the movie won’t be very interesting.

Let’s take a look at an example screenplay and break it down.

Terminology

Slugline – At the beginning of every scene, we have something called a slugline. In this example, the slugline is

“INT. KITCHEN – HOUSE – DAY.”

Sluglines consist of three main parts. First, we have INT. or EXT., meaning interior or exterior. If the scene takes place inside (a house, a coffee shop, a store, etc.) the abbreviation INT. is used. If the scene takes place outside a location, the abbreviation EXT. is used. The second part is the location itself. You might have a few of these in a row if the location is very specific or notably important, like:

“INT. KITCHEN – HOUSE – RURAL STREET – NEW YORK – DAY.”

The final part of the slugline is the time of day. Generally, screenwriters stick to either “DAY” or “NIGHT” but other times (morning, noon, afternoon, evening, dusk, sunset, midnight) can be used.

Parenthetical – A parenthetical appears below a character’s name but above their line of dialogue. These are usually just a few words enclosed in parentheses that describe how a character is saying their line. Parentheticals should be used sparingly – only for descriptions that aren’t obvious. Parentheticals can be useful because they make the writing flow better by replacing a sentence of description.

Transition – “CUT TO”, “SMASH CUT TO”, “FADE TO”, and “DISSOLVE TO” are all transitions. They indicate different ways to move between scenes. “CUT TO” is the most common. “FADE TO” is typically used for dramatic scenes, while “SMASH CUT TO” might be used in fast-paced action scenes (this is essentially a faster cut). Star Wars is famous for experimenting heavily with its camera transitions. These usually only show up in shooting scripts. The one exception is “FADE IN” which is how almost every screenplay begins.

o.s. “o.s.” simply means “offscreen.” This abbreviation is used (next to a character’s name before their dialogue) if we hear a character speaking but cannot see them in the frame.

v.o. “v.o.” is the abbreviation for “voice over.” We use this, like “o.s.,” next to a character’s name. This one is used if a character is not present in the scene at all and is speaking in the background, as if to the audience.

Other Terms

ROLL CREDITS – This term is used to indicate that the movie credits appear on the screen.

INT./EXT. “INT./EXT.” can be used in place of “INT.” or “EXT.” in the slugline. This means “interior/exterior”. A common use of INT./EXT. is when a character is in a car, because they might be outside, but are physically in their car.

CONTINUOUS – “CONTINUOUS” can be used at the end of a slugline to note that we are switching locations in one shot. For example, if the camera follows a character walking out of a store into a parking lot, CONTINUOUS might be used in the new slugline to suggest the transition.

MUSIC UP – This is used along with a song title and artist and indicates that a song is starting. Song titles, along with any other sounds mentioned in a screenplay, should be capitalized.