Female Sarcasm? If You Hear It, You Should Ponder It

Such Words Transmit Messages About The Missteps of Social Assumptions

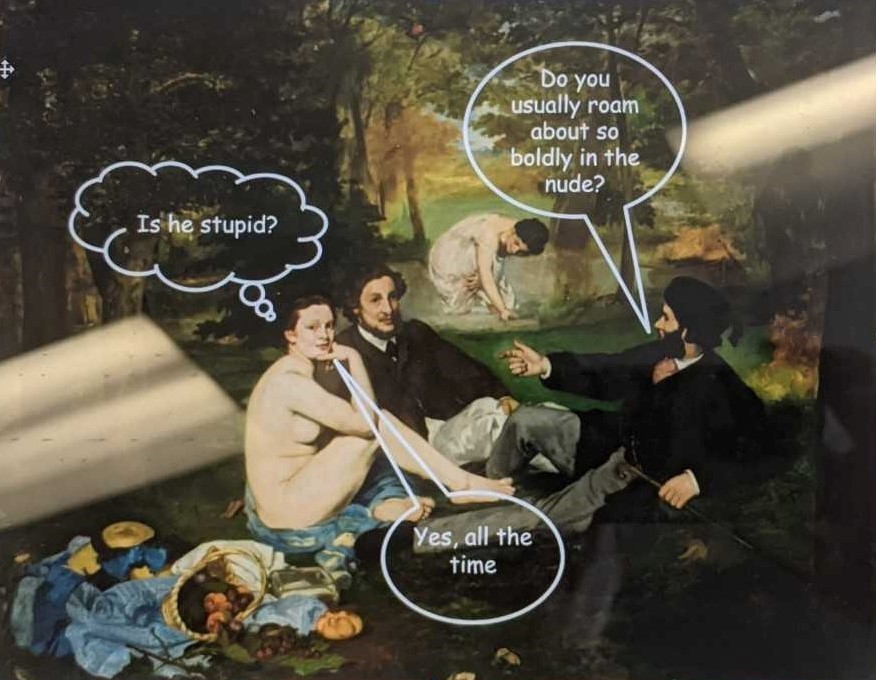

(Image of Original Painting: Manet.org)

“The Luncheon on the Grass” by Édouard Manet, currently on display at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. Text and thought/speech bubbles added by author.

March 5, 2023

“So, are things hopping on the boys’ scene?” a party guest, forty years our senior and reeking of alcohol, asked my friend and I as he stumbled onto the couch next to us. I watch my friend take a deep inhale and smirk to myself knowing what’s about to happen.

My friend looks him dead in the eyes, and in a monotone voice replies, “Oh, yeah, I’ve got three boyfriends, but it’s getting too difficult trying to keep ‘em separate.” The man’s eyes bulge and don’t return to their glassy state until he catches on to her joke. He tuts at her and sulks off. He was not prepared for a confident response to an inquiry about boys (notorious for making girls blush and stutter over their speech), nonetheless a sarcastic one.

But women’s powerful use of sarcasm extends to more than silly little jokes about boys — shocking, I know. In her autobiographical graphic novel Persepolis, Marjane Satrapi recounts her time as an Iranian expat in Vienna during the Islamic Revolution. She was exposed to more trauma and atrocities than most young Western Europeans at that time, so when her “enlightened” Austrian friend Mono tells her that believing in a meaningful existence is only a distraction from the boredom of living, her response is, “Yeah, and my uncle died to distract himself” (194). Like the inebriated partygoer, Mono didn’t react to Marji’s sarcasm other than to widen his eyes. They didn’t know what to make of the sarcasm in our speech, so they simply ignored it. Marjane doesn’t want to be neutral when her friend makes an inane and insensitive remark. But again, he doesn’t say anything when she counters him. He has the luxury of silence: If he didn’t reply to Marji, he would still be in power; if Marji kept silent after his imposition, he would still be in power. Seems fair.

Too often this story is repeated: We, as women, are asked an inappropriate question, pestered to smile (98% of women have reported a male colleague telling them this), ordered to do something we don’t want to do, or made to listen to something preposterous with which we disagree. Society dictates that we always listen and reply respectfully. When our response is sarcastic, suddenly we’re the one who’s offensive, our speech is improper. Countless Hollywood actresses have gone on the record about how their sarcasm is misinterpreted. Take Aubrey Plaza, noted for her roles in the TV show Parks and Rec and The White Lotus, who’s berated in the industry for her inexplicable sarcasm, which is deemed “unladylike.” She claims she uses it as a “defense mechanism” to events she deems unnatural like the warped conceptions of fame and celebrity. If the public could open their ears a bit wider, they could hear sarcasm’s deeper meaning: to refute patriarchal power and refuse its demands of our behavior.

Women’s use of sarcasm has developed into (or perhaps, always was) a political and social tool. As noted by Lori Ducharme, a professor of Sociology at the University of Georgia, among its comedic and offensive uses, sarcasm can be used with the intention of “maintaining group boundaries” in order to outline “what activities are expected and tolerated of members”. From girlhood, we are under intense pressure to conform to a “socially acceptable” girl: placid, docile, and all of the other–frankly, boring–character traits that are easy for men to invalidate. The minute I am slightly acerbic and not eager-to-please, the sirens blare: *She’s not being nice! She’s not being submissive!* Could it possibly be that I am saying: “No, you crossed a boundary. I am not passive. I am neither prim nor proper, and I don’t have to be for you to respect me?” Studies have even gone so far as to link the brain’s perception of sarcasm with contextual background. Maybe, just maybe, my sarcasm is larger than me. Maybe it’s a culmination of all the ways in which girls are manipulated and made to feel insecure so the patriarchy can have its way. But, what would I know? I’m just a girl.

We need to start listening to women when they use sarcasm because it’s often a signal that something’s off in our environment, an intimation that the line in the sand is misdrawn, and an exemplar of how we can effectively eradicate patriarchy from our speech. Of course, we shouldn’t read too much into teenage girls’ sarcasm; it’s nonsense anyways.