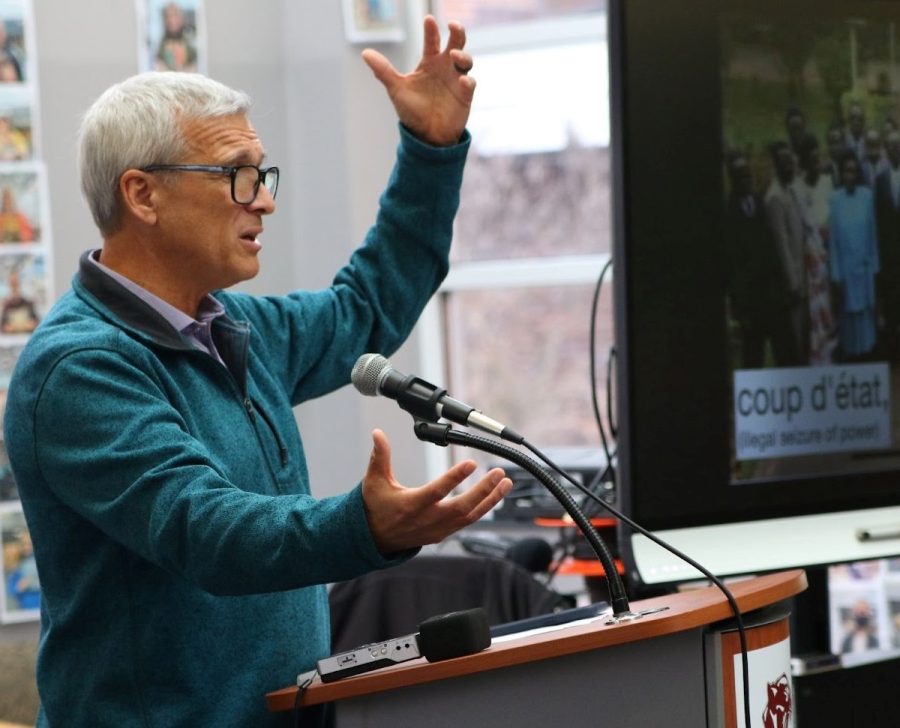

Carl Wilkens, Student Perspective: Speaker’s Story Makes Emotional Connection

Genocide Class Members Hear of Tragedy First Hand

Carl Wilkens spoke of his experiences in Rwanda, showing why a Genocide course is so important.

March 7, 2023

Amid midterm exams, final essays, and the general slog of January, Mr. Goldman’s Genocide class remained hard at work. Why? Because of an impending visit from Carl Wilkens, a former missionary worker and survivor of the Rwandan genocide. Though the class had focused mostly on the Holocaust, the last few weeks were spent researching the Rwandan genocide and getting ready to host Wilkens– and he certainly did not disappoint.

Carl Wilkens’s hair is white now, but back when it was dark brown, he and his family moved to Rwanda from the United States. They had lived there for 4-5 years when the genocide began. Provoked by a plane crash that killed former Rwandan president Juvénal Habyarimana, underlying tensions between two cultural groups (the Hutus and the Tutsis) erupted into the bloodiest 100 days since the end of World War II with the Hutus systematically targeting and exterminating nearly the entire population of the Tutsis. Due to the threat, many foreigners were urged by the UN and the United States government to evacuate the country. Carl Wilkens however, believing it unfair to leave those whom he called friends and family to face their deaths, decided to part ways with his immediate family and stay in Rwanda.

To find out more about Wilkens’s intentions and about the event itself, you can read the article “A Conversation with Carl Wilkens” by Emerson Dyer and Jenna Moore. Here we will examine more closely just how the event impacted the students who attended it.

When put into the perspective of a mundane high school life, experiences like Wilkens’s seem hard to grasp because reality can often feel dull. It’s hard to channel real empathy for something we’ve never lived through at such a young age, so to discover how students really connected with his story, I surveyed 11 upperclassmen about their experiences among the audience.

Most students (unless they were in Mr. Goldman’s genocide class) had no prior knowledge of the event except for maybe a brief summary their teacher had given them before taking them down to the library to see the event. Even with their limited background knowledge though, many students said that they felt emotionally moved by Wilkens’s speech. One student stated that she felt grief along with Wilkens while he was telling his story. William Connolly also felt moved by Wilkens’s storytelling abilities. “It wasn’t so much what he was saying, but how he was saying it,” Will said.

Students who were enrolled in Mr. Goldman’s genocide class came to the event with much more background than those who weren’t, but even they reported that at least some of the experience did not resemble what they had imagined. Emerson Dyer said she “didn’t expect to be affected by [Wilkens’s] presentation that much,” and that she “felt choked up… when he was talking about the conversation he had with his Dad about him staying in Rwanda.” She said she knew she would have had to have the same conversation about her own desires differing from her Dad’s had she been in Carl Wilkens’s shoes. In that way students were able to relate to an experience they will likely never have to face. The heartfelt and conversational way that Wilkens spoke and the kinds of personal stories he told provided a basis for students to connect his life to their own. One student said that his emotionality helped him connect to the story, stating that he “had some previous knowledge of [Wilkens’s] experiences…, but some parts of what he talked about can just never be expected.” Jakob Sauve reported similarly saying that he also felt emotional during the speech. He said that “Mr. Wilkins’s story is packed with heroism and close calls that could’ve been fatal to him. The fact that he was able to save so many lives… is amazing.”

Towards the end of his speech, Wilkens divulged a story about going back to Rwanda after the genocide many years later that provides an example of the heart wrenching experiences he shared. He told about a Tutsi woman he had known named Maria whose sons were killed in the genocide. When he was there, he found out that she was now close friends with the man who had killed them. When he told us about it, he said initially he was horrified that anyone could forgive such an awful thing, but then it made him take a step back and consider that “who you were is not always who you will be or who you are.” This was a part of his talk that many different students found impactful. One student said she “found [herself] tearing up when he got emotional within his speech because it showed the impact of Rwanda on him” and that this story in particular “inspired [her] to view empathy differently.” Wilkens learned that Philbert, the killer of Maria’s sons, helped around the house and cared for the aging woman in the same way that her sons would have if they were still alive. He overcame that initial shock by realizing that though it can be painstakingly difficult, forgiveness and, on a larger scale, restorative justice — a word used to describe a process of justice where criminals are rehabilitated rather than punished — is ultimately more beneficial than playing an endless blame game.

Jackson Smith spoke on how Wilkens’s view of forgiveness impacted him in his response saying that the “idea of forgiveness can be really strange and hard to grapple with… In American culture specifically we tend to emphasize the idea that people need to be punished for their actions. . . . The idea that Rwanda was able to establish a justice system built around forgiveness” and turn its history on its head “is proof enough that forgiveness is at least worth considering.” He believes that the rest of the world should look to Rwanda for inspiration.

Wilkens’s story is incredibly moving, and it seemed to resonate with much of the student body present. However, while Carl Wilkens was in the middle of a sentence about restorative justice, the bell rang. A perfect E flat rang high above the school, reminding us that time here only moves in 56-minute intervals. Moments later the hallways roared with students changing classes. How does one arrive at their next class and return to their normal routine after witnessing such an emotional speech?

William Connolly described feeling “woozy” from the “dissonance of going from such calm discussion of such heavy subjects back to normal life.” He was one of the few people who was able to ask Carl Wilkens a question after the event. When he got to math class late he said his “head was spinning,” adding, “it was impossible to go back to velocity and acceleration after what [he’d] heard.” Jenna Moore agrees and said that events like the one held on January 24th hold a level of “realness” and “directness” to them. She concludes that “many people see the Holocaust or Rwanda, Cambodia, Armenia, as a number, or a statistic, but when you’re face to face with these people, who experienced a genocide close up, it’s just unbelievable how it can impact you.”